Fountains Abbey is in ruins. I liked this church very much, as the structure, not the decoration, was the emphasis. No windows, statues, mosaic floors (except for one)–just the walls, the layout and the gloriously sunny sky. This was one of our more well-documented sites, so please forgive the number of photos.

The abbey ruins are approached from walking through pastures above the site, and the tower aside the north transept is visible just over the trees. We read from the guide pamphlet as we walked around, and I’ve excerpted some of it below.

The abbey ruins are approached from walking through pastures above the site, and the tower aside the north transept is visible just over the trees. We read from the guide pamphlet as we walked around, and I’ve excerpted some of it below.

A group of monks left St. Mary’s Benedictine Abbey in York in 1132 to found a more devout monastery. One of their vows was not to be within an arm’s length of each other, so this abbey is very large in scale, although it only housed about 80 choir monks.

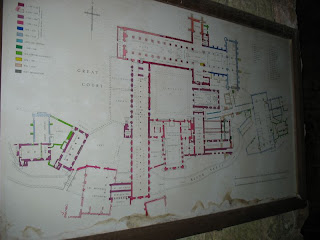

This is the view taken from the abbey guest house, also in ruins. I found a map (later in this post) that identified what all the parts of the structures were at one time, plus I’m getting the hang of this church logo after all the churches we’d toured thus far in our trip.

This is the view taken from the abbey guest house, also in ruins. I found a map (later in this post) that identified what all the parts of the structures were at one time, plus I’m getting the hang of this church logo after all the churches we’d toured thus far in our trip.

The side corridor flanks the nave, with small hollows where chapels used to be. Most of the abbey buildings date from between 1140 and 1270, though the north tower was added during King Henry VIII’s reign.

The side corridor flanks the nave, with small hollows where chapels used to be. Most of the abbey buildings date from between 1140 and 1270, though the north tower was added during King Henry VIII’s reign.

Through the roof and side chapel to the tower. We weren’t allowed underneath to look up: falling rocks.

Through the roof and side chapel to the tower. We weren’t allowed underneath to look up: falling rocks. The window over the front door. This little settlement at Fountains was part of the austere Cistercian Order.

The window over the front door. This little settlement at Fountains was part of the austere Cistercian Order. The only mosaic left was the altar floor. The abbey was closed down in 1539 and the Abbot, the Prior and the monks were sent away with pensions. The estate was sold by the Crown to a merchant, and remained in private hands until the 1960s.

The only mosaic left was the altar floor. The abbey was closed down in 1539 and the Abbot, the Prior and the monks were sent away with pensions. The estate was sold by the Crown to a merchant, and remained in private hands until the 1960s. Between the high altar and the huge window, was an area they identify as the Chapel of the Nine Altars. This view is looking toward the north side of that area.

Between the high altar and the huge window, was an area they identify as the Chapel of the Nine Altars. This view is looking toward the north side of that area. Looking from the south side of the Chapel of the Nine Altars through to the infirmary passageway walls.

Looking from the south side of the Chapel of the Nine Altars through to the infirmary passageway walls.The nave is the portion of the church that runs from the front door to the back window, and the transept runs crossways, forming a cross-shape. At that intersection in this church is the choir and, except for the built-in seats, is indistinguishable by any remnants. Maybe it was because in the early 17th century, Sir Stephen Proctor build a mansion using sandstone blocks and a stone staircase from the abbey. However I’m sure this cleaned-up version of an abbey that we see now happened only after carting out tons of fallen rock.

Several groups of school children were there. They donned habits to emulate the monks. The 80 choir monks were known as “white monks” because they wore habits of undyed sheep’s wool. The lay brothers worked the farms (or granges) that belonged to the abbey and they wore darker wool. They may have numbered several hundred in the early years.

Several groups of school children were there. They donned habits to emulate the monks. The 80 choir monks were known as “white monks” because they wore habits of undyed sheep’s wool. The lay brothers worked the farms (or granges) that belonged to the abbey and they wore darker wool. They may have numbered several hundred in the early years. We are on the south side of the cloister, a large square area that is on the other side of the side corridor of chapels. They are passing what would have been the doorway to the Chapter House. (I have no idea what that is.)

We are on the south side of the cloister, a large square area that is on the other side of the side corridor of chapels. They are passing what would have been the doorway to the Chapter House. (I have no idea what that is.) The Cellarium, or as they refer to it on the map, the Lay Brother’s Refectory. They had a separate eating area for the monks. One end of this was for their “stores” and the other is where they ate. It’s all mossy and green, but intimate with its low, yet vaulted ceiling.

The Cellarium, or as they refer to it on the map, the Lay Brother’s Refectory. They had a separate eating area for the monks. One end of this was for their “stores” and the other is where they ate. It’s all mossy and green, but intimate with its low, yet vaulted ceiling. We took the “High Ride” walk up in the forest to Anne Boleyn’s Seat and Surprise View. The Half-moon Pond is a nice counterpoint to our surprise view.

We took the “High Ride” walk up in the forest to Anne Boleyn’s Seat and Surprise View. The Half-moon Pond is a nice counterpoint to our surprise view. John Aislabie inherited the estate in 1693. He was the Member of Parliament for Ripon and became Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1718, but was discredited for his part in a financial scandal just two years later. After spending some time in the Tower of London, he retreated to this estate and threw himself into plans to create a formal water garden in the River Skell Valley. This project kept him busy for the rest of his life.

John Aislabie inherited the estate in 1693. He was the Member of Parliament for Ripon and became Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1718, but was discredited for his part in a financial scandal just two years later. After spending some time in the Tower of London, he retreated to this estate and threw himself into plans to create a formal water garden in the River Skell Valley. This project kept him busy for the rest of his life.

The Temple of Piety was first named Temple of Hercules, perhaps to commemorate the huge labor of constructing the garden. In 1768, the temple was furnished with “six chairs, a tea table and a little stand,” which gives us an idea of how it was used in his day.

A statue of Neptune, the Roman sea-god (1740).

A statue of Neptune, the Roman sea-god (1740).William Aislabie, John’s son, took over and worked on some of his own ideas from the garden, fashioning it into a more natural state, which was popular at the time. In 1768, he managed to buy the abbey ruins, “securing the romantic vistas along the valley,” says the guide sheet. The High Ride walk (with the Surprise View) was his creation. He holds the record as the MP with the longest period of continuous service: 66 years.

“The Cascade” is a the last small falls in the Water Gardens, but the place where John Aislabie began construction. The work took three years, as nearly 100 men were needed to dig the canal.

“The Cascade” is a the last small falls in the Water Gardens, but the place where John Aislabie began construction. The work took three years, as nearly 100 men were needed to dig the canal.

We didn’t see everything, but enjoyed the day in the gardens. Stopping back by the visitor center, we had a bite to eat before driving further into Yorkshire.